“...aria infiammabile nativa delle paludi...”

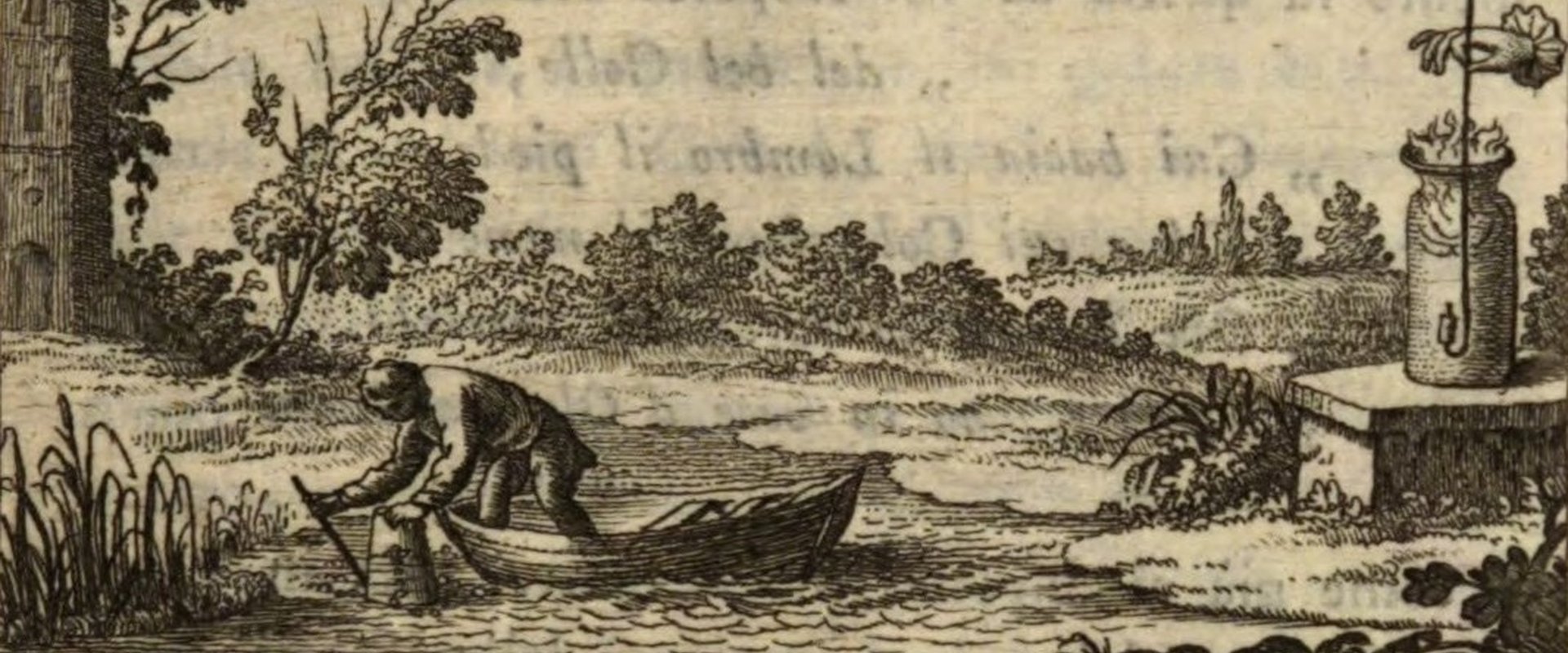

By Jens Soentgen und David Gottfried Over centuries, the air of wetlands has been at the center of their negative image. Physicians warned that the air of “swamps”, but also of any stagnant water may cause pestilence. Such health risks were only one aspect. Through its appearance, the air proved to be uncanny and eerie. In this strange, water-filled atmosphere, ephemeral fires can occur. For centuries, folklore has described these ephemeral fires as will-o'-the-wisp phenomena, atmospheric ghost lights that tried to distract nightly travelers from their chosen pathways and leading them into the dangerous areas of the bog. By the way: Even one of the “Founding Fathers” of the United States of America was interested in wetland atmospheres. In 1774, Benjamin Franklin wrote a letter to Joseph Priestley, in which he described inflammable wetland air. He explained the phenomenon as turpentine oil from pine trees mixing into the waters, causing them to be partially flammable. His explanation however was deemed “a little too credulous” by his colleagues, as he writes himself. Alessandro Voltas’ theory of inflammable air, which he discovered two years later, should prove to be more credible, as we know today. Sources and literature: - Benjamin Franklin to Joseph Priestley, 10 April 1774, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-21-02-0078. [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 21, January 1, 1774, through March 22, 1775, ed. William B. Willcox. New Haven and London 1978, 188–189.]

Alessandro Volta and the flammable "swampair"

Using gases from wetlands to power a gun? In the 18th century, that was planned and realized by the Italian naturalist Alessandro Volta. Volta’s pistol uses methane (he called it “aria infiammabile nativa delle paludi”), an inflammable gas, which he discovered in the air in wetlands, at this time more generally referred to under the name of “swamps”.

Early modern physicians such as Bernardino Ramazzini collected examples of professions that were often exposed to fowling bad air and gave recommendations on how to avoid exposure. However, more precise precautionary measures could only be achieved when pneumatic chemistry succeeded in isolating and identifying types of air that were recognized as components of normal air. Experimenting in wetlands around Lake Maggiore, Alessandro Volta could demonstrate how the foul-smelling gases contained a new type of air, which was, excitingly for the scientist, flammable. The observations of Volta and those of the British scientist Joseph Priestley and their widespread translations opened up a new field of research on combustible gases and methanogenesis that developed in the 19th century and expanded into the 20th century. Over the course of time, scientists objectified the putrid odors that emanated from the “swamps” into putrefactive gases. They analyzed them as mixtures of methane, hydrogen sulfide, and other gases mixed with trace gases, such as various phosphorus compounds.

It is worthwhile to investigate how wetland atmospheres were perceived between 1700 and 1816 and what effects, particularly of a physical and medical nature, were attributed to them. A turning point in the period under investigation was the discovery of what was at the time known as flammable marsh air, now known as methane. For some time, this gas was blamed for all the health problems endemic to wetlands. Although this interpretation soon proved to be premature, the specific type of air first discovered in the marshy regions of Lake Maggiore was nevertheless a significant chemical, meteorological and medical discovery.

- Volta, Alessandro: Lettere del Signor Don Alessandro Volta, patrizio comasco, e decuriore, regio professore di fisica ... sull'aria infiammabile nativa delle paludi, Milano 1777.

- Eckartshausen, Karl von: Über das Verderbniß der Luft, die wir einathmen, ihrer Schädlichkeit für die Gesundheit der Menschen, und die Art, sie leicht und schnell zu verbessern. 24. März 1788, München 1788.

- Hsuan L. Hsu: The Smell of Risk. Environmental Disparities and Olfactory Aesthetics, New York 2020.